Post-Project Community

GALLERY 1

Contributor: Tom Heldal, Norway

Subject: Iddefjord Granite

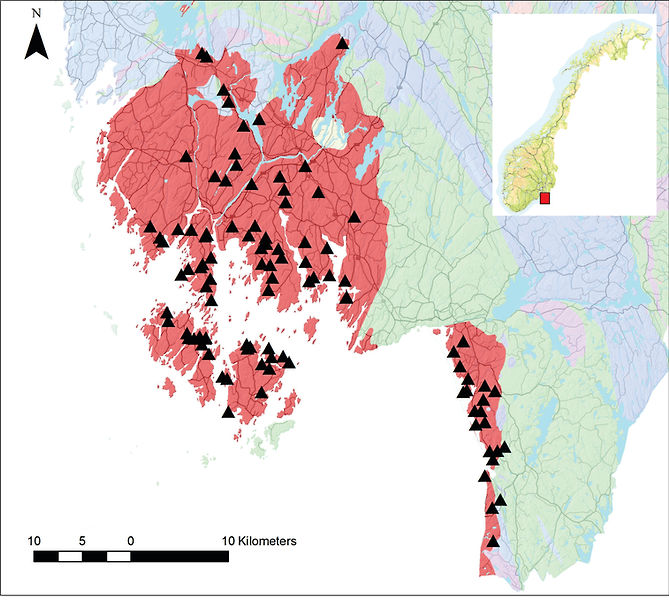

Iddefjord granite (Norway)

One of the most important quarrying districts in Norway is linked to a Late Precambrian granitic complex, often referred to as the Iddefjord Granite. Although minor quarrying took place already in the 12th Century, it was the industrial revolution that triggered large-scaled granite quarrying in Norway. From the 1850s onwards, the production grew, culminating just after the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when 5000 workers worked granite in hundreds of quarries.

The Iddefjord Granite is grey to pinkish, but the main advantages are its unique quarrying properties (block size and workability) as well as extreme durability. Thus, the district delivered stone for many purposes in Norway, but also abroad, such as the Ritz Hotel in London, streets of Buenos Aires and docks of Cape Town. The granite is a high-quality material for sculptures, like those you see at the Vigeland sculpture park in Oslo.

At present, the stone industry in the district is small but sustainable. You can find footprints of the past quarrying in the terrain, and several trails will lead you through ancient quarry landscapes. A rare example of documentation of traditional skills is found in a film from 1966 (text and audio are in Norwegian, but the video is quite self-explanatory).

GALLERY 2

Contributor: Tom Heldal

Subject: Cezanne's quarries, Aix en Provence

Tom Heldal

Cezanne and his beloved quarries (France)

Paul Cezanne was one of the most important post-impressionist painters laying the foundation for 20th century art, and was based in Aix-en-Provence. One of his favourite places was the Bibémus quarries on a hill above the city. Here, sandstone for the construction of the monumental architecture of the city were exploited from the Roman period onward until the 18th Century, leaving a pronounced geological fingerprint on the architectural heritage.

The old quarries make a fascinating landscape of human made cliffs, displaying marks from thousands of quarrymen carving the mountain with picks. Today, Bibémus Quarries is an open-door museum where you can literally walk in the artist’s footsteps and brushstrokes. The museum claims that this is the birthplace of cubism. At least, it is an example of how a site for extracting raw materials for monumental architecture became a monument itself. And, about the intimate connection between a quarry landscape and the city and people it served through millennia.

GALLERY 3

Contributor: Tom Heldal

Subject: Lapiz Specularis, Italy

Lapiz Specularis: the window stone (Spain)

We know that natural stone can be used to build walls, pathways, roads, panels, ornaments, sculptures and even utensils. Stone is solid, durable and beautiful material, ready-to-use from Nature. But one particular historical use of stone stands out. Who would think of using stone slabs for windows? Well, the Romans did!

5.5 million years ago, the access between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean was closed due to tectonic forces, and a large part of the Mediterranean dried out, much like like the Dead Sea is drying out today. As a result, large deposits of gypsum formed as the sea evaporated, creating the land mass we know today as Spain.

In some areas, gypsum appeared in the sedimentary layers as huge, transparent crystals, many several meters in length. Ancient craft people would carefully removing surrounding rock with picks to expose the high quality, and often transparent crystals. The Roman stone workers would slice the stone into thin sheets to be used as windows.

The people of Arboleas, Almeria, are investing and contributing a lot of voluntary time to excavate and prepare one of the Roman mines for visitors. The site is truly spectacular, from both a geological or historical point of view. And, in Cartagena, as in Pompei, we may view examples of how a strange, transparent stone was applied in antiquity. While we no longer use gypsum for windows, today we use vast amounts of gypsum in construction, much of which is extracted from ancient deposits, that once belonging to the Roman Empire.

GALLERY 4

Contributor: Tom Heldal

Subject: Cipollino Verde (Greece)

Cipollino Verde (Greece)

At the southern part of the island of Evia, Greece, large deposits of a unique type of marble are found –the Cipollino Verde. This was one of the most popular coloured marbles of the Roman Period and examples of its use have been found in almost every corner of the Empire as far north as Britain. Production probably started in the 2nd Century BCE and continued through the Imperial Period until the 7th Century AD. The Romans called it Marmor Karystium after the small town Karystos on the southern tip of the Island. The Cipollino Verde is an impure calcite marble containing bands rich in silicate minerals, displaying a lively pattern of folded and sheared layers. The marble can still be purchased through several ornamental stone suppliers.

GALLERY 5

Contributor: Tom Heldal

Subject: Oppdal Schist (Norway)

Oppdal Schist (Norway)

Schist that can be split along natural cleavage planes into either thick or thin slabs is a common and important stone resource in Norway. One of the most important schist deposits in Norway is located close to the village of Oppdal, Trøndelag county. Once deposited as sand layers on an ancient, continental margin, metamorphism and tectonic processes during mountain building made the hard, cleavable rock so desired today. While schist has been produced in Oppdal for a few centuries, the craft of extracting and splitting schist slabs can be traced back about one thousand years. Today, several companies produce schist in the area, applying both traditional craft and new technology.

GALLERY 6

Contributor: Mirka Trajanova

Subject: Pohorje granodiorite (Slovenia)

The Pohorje granodiorite (Slovenia)

Though Slovenia is relatively rich in natural stone, quarrying in igneous rocks is limited only to the country’s northern part, to the Pohorje Mountains, a tectonic block belonging to the Austroalpine units of the Eastern Alps. Central part of the block is intruded by the Early Miocene medium-grained grey granodiorite, but locally also tonalite is present. Frequent white aplite-pegmatite veins crosscut the intrusion, which give the rock a unique appearance. Though covering an area of over 200 km2, exposures suitable for exploitations are rare due to Late Miocene brittle deformations and extensive weathered areas in the central part. Four quarries were active in the past (Cezlak, Hudi kot, Josipdol and Recenjak) of which only the one near the Cezlak Village is still in operation (quarry Cezlak I).

Interesting at sight and durable, the rock in Cezlak attracted interest of people already in the 19th century, when local farmer Cezlak started small extraction in 1891. From then after, ownership changed several times. Bigger production started in 1910 under the ownership of Windischgrätz when the first investigations were carried out. Mainly paving cubes and blocks for construction of bridges were produced. After World War the Second, the production and the market size were growing. Good workability and physical-chemical characteristics lead to products diversification and the rock became one of the most significant natural stones in Slovenia. Numerous architectural details are made of granodiorite, and some important buildings decorated: the Slovenian Parliament, the Republic Square business complex, the Faculty of Law of the University of Ljubljana etc. The granodiorite is also exported, mostly to Austria, Germany and Switzerland.

GALLERY 7

Contributor: Christian Uhlir

Subject: Mönchsberg Conglomerate

A “natural concrete”: Mönchsberg Conglomerate

At first glance, it seems that the city of Salzburg is built of pebbles. Lining the walls of alleyways and streets; forming sacral and civil monuments and part of Salzburg’s old fortification, we find Mönchsberg conglomerate. Historically, this distinctive stone was used near its source - cut and shaped. Built structures often blend into the abandoned quarry walls that are now part of the city.

It was an easily accessible, extremely local, workable material that was used from the Roman times up to the middle of the 20th century. Combined with the elaborate architectural features, the aesthetic effect is pleasing.

The area of Salzburg was once an interglacial sea and this rock type was formed of delta deposits within that lake during the Mindel-Riss interglacial. Over time, the gravelly components, limestones, gneiss, greenstone and quartzite, were cemented together chemically with carbonate. When the glaciers retreated, the conglomerate layer remained in the region as hills.

Mönchsberg conglomerate, dark grey to brownish colour, is all around you in Salzburg. But today, the new facades of shops and houses are made of material imported from the south of Vienna - the Lindabrunn conglomerate.

For more geological information, please download one of the interpretive posters (German and English) which visitors find at the fortification site and read more about this and other ornamental stones used in Salzburg here (Uhlir et al., 2010)

GALLERY 8

Contributor: Matevž Novak & Snježana Miletić

Subject: Podpeč limestone (Slovenia)

Podpeč limestone (Slovenia)

The history of stonecutting in the village of Podpeč goes back to the 2nd century when limestone blocks were transported shipped down the Ljubljanica River 11 km north to the Roman outpost of Emona (present-day Ljubljana). Following the demise of the Roman Empire the demand for the beautiful black limestone dried up and it was not until the late 18th century that it started to revive. After the devastating earthquake that shook Ljubljana in 1895 large amounts of limestone were quarried for the restoration of the city. Its decorative value became appreciated again in the 20th century, especially by the internationally renowned Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik (1872-1957). His beloved stone is embedded in many of Ljubljana’s buildings including the National and University Library, the Ljubljana Skyscraper and in the marketplace arcades.

The most beautiful, if not the most common, variety of the Podpeč stone is black dense limestone with white cross-sections of lithiotid bivalves. The lithiotids are middle Early Jurassic (190–180 Mya) fossils with a shape some-what resembling the recent pen shell. In some beds in Podpeč quarry the lithiotids can be seen preserved in their living position.

Besides lithiotids, the limestone offers a glimpse of other forms of life in the ancient Jurassic lagoon on the Dinaric Carbonate Platform: other bivalves, gastropods, brachiopods, corals and foraminifera. Oolitic varieties suggest that sand bars protected the lagoon from the open sea. The Podpeč limestone has been designated a Global Heritage Stone Resource (download pdf) in 2017.